As journalists, we often find ourselves reporting far away from where we live. Or on issues disconnected from our home.

The bulk of journalism in Malaysia, as I can observe, revolves around federal politics. This means long days in Parliament asking politicians about national policies and laws. Or doorstopping policymakers outside government agencies or government events. Don’t forget the endless press conferences. For whatever reason, this has led to reporting that often resembles political gossip.

The respite from this grind is being able to travel further from home, to report on issues such as climate change, human interest, or the odd international story.

Even stories that are inherently local – local floods, local development issues, local government issues – are usually reported on by journalists who don’t actually live in that area.

To get the most out of this toolkit, check out the multimedia story I produced on my own neighbourhood:

This story relates to a land dispute affecting the neighbourhood in which I am living. Having decided to produce an investigative story on the issue, I applied for grant funding and received a moderate amount of funds that allowed me the time and resources to research and publish the story.

Read a full report on the production process

After publication, the short documentary went viral, attracting 1.7 million views and over 2,000 comments within two weeks. The multimedia story has registered 27,000 page views as of 7th December 2023. The public attention led to two mainstream publications producing coverage of their own on the story:

It also caught the attention of the government. The state assembly person (ADUN) of the area immediately reached out to residents to offer financial assistance for the apartments’ common area utility bills. She also offered to seek funds to purchase the land from the landowner.

At the hyperlocal level, the story reinvigorated discourse among neighbours, with neighbours seeking out more information about the issue, sometimes by contacting me directly.

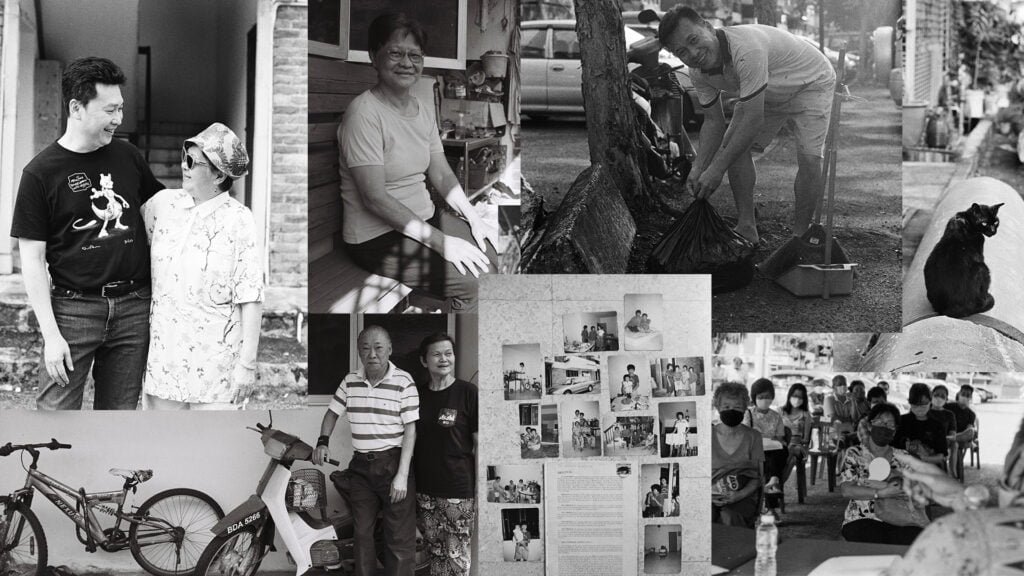

I also observed increased participation in the neighbourhood, with communal gotong-royong activities organised to counter the lack of cleaning services caused by the ongoing land dispute.

Reflection

Well, I’d say that the process is much like any other reporting process. Each newsroom or journalist will have their own process of identifying, researching and producing a story. However, drawing from my experience producing The Apartments With No Entrance, I’ve identified a few lessons that I think will make your reporting experience more fulfilling, and your story more powerful.

To start, it might be worthwhile preparing yourself with the right approach, and a good grasp of the context.

It all starts with being involved enough in the neighbourhood, to be able to know when there are challenges that would need your skills as a journalist.

In any neighbourhood, there is usually some form of local community organisation, either formal or informal, through which the neighbourhood makes decisions. This could be the area’s residents’ association (RA), or an apartment’s management council (MC), or a village’s Jawatankuasa Pembangunan dan Keselamatan Kampung (JPKK). Finding out how your community is organised would be a good first step.

Then, attending the activities and meetings of these organisations will help you get involved further. Bodies such as RAs and MCs are required to hold annual general meetings, where decisions affecting the neighbourhood are made. Residents are usually notified in advance of these meetings, which are often a platform for residents to air concerns as well. Make time to attend these meetings, and get to know the people who are already involved. When there is a need for your skills as a journalist (writing, photography, research, etc.), try to make yourself useful.

There are also informal ways to be involved in your neighbourhood – for example, being available when neighbours ask for help, or simply getting to know as many of them as possible.

I have found this to be a good practice in any form of investigative reporting. Compile this from available information – media reports, archives, official documents, etc – on a spreadsheet, with links to your sources of information. This process gives you a good overview of the issue you are investigating, and knowledge of the information that has already been made public so your story will not merely be a regurgitation of available information.

To reference the chronology of events compiled for The Apartments With No Entrance, click here.

The exercise of compiling a chronology of events can also function as a test of your story’s hypothesis. For example, my initial hypothesis was that the subdivision of the land was done when the developer applied for strata titles in 2000. However, research to compile a chronology showed that the subdivision was done in 1966, before construction on the apartments began. This led me to focus on other leads, such as the details of the land sale, and the relationship between the developer and current landowner.

Bear in mind that you will be in close contact with neighbours throughout this reporting process, and even after the story is published. You will be their neighbours long after your role as a journalist ceases.

In this case, I’ve found it useful to draw from a communitarian media ethics framework in approaching the story, where the common good of the community is the end goal, and truth-telling is merely the means.

What is the common good for the neighbourhood that I am looking to achieve through my reporting? Do neighbours see things the same way? How can my reporting help achieve this?

Knowing the role your reporting plays in your neighbourhood’s wellbeing means you can help neighbours understand it too. This will stand you in good stead throughout the reporting process.

But how are you going to get the story to the public? Well, you’ll need to…

Having done research for the chronology of events, you now have a decent understanding of the issue and the likely angle your story will take. Now, you’ll need a way to get your story published, so it reaches the public. If you are working at a news organisation, build a story pitch and bring it to your editor, much like you would pitch other stories. The difference is you can show the access you have to your residents and your existing understanding of the neighbourhood as a resident yourself. This should help your pitch stand out. Your editor has the role of keeping you unbiased, so that shouldn’t be a concern.

It’s a bit more complicated if you’re an independent journalist. You can either choose to find a publishing partner, or self-publish. Best to reach out to publishing partners through personal connections. In my case, The Fourth was a reliable publishing partner.

You’ll also need to decide what form your story will take. Will it be a written article? A documentary? At this point, this plan will be tentative, as things will change as you investigate further.

I would also suggest drawing up a detailed schedule with deadlines for investigations, completion, and publishing. Try to stick to these deadlines. This is because reporting within your own neighbourhood, can feel like a calling more than a job. In my experience, this led to delays as I continued researching different leads trying to find conclusive evidence. Instead of insisting on producing a conclusive investigation, publish with what you have when you reach the deadline, then set aside some time after publishing to produce follow-up stories. Your initial story might lead to new information or responses that are worth reporting on.

I won’t get into the usual journalism processes involved in investigating and producing a story, I’ll assume you have your own processes already. If you would like to know how I investigated and produced The Apartments With No Entrance, you may refer to the full report here.

However, I’ve found that reporting on a neighbourhood issue requires a few adaptations from the journalist. Here are some key lessons I learned:

Oral history in this situation would be the first-person lived experiences of your neighbours. To prioritise oral history does not mean to completely discard documented or official narratives. It means that the facts of the story are set in the context of your neighbours’ lived experience. Try to find out how and why their lived experience contradicts or departs from the official narrative.

Then, in your story, prioritise showing how the issue you are investigating has affected, or continues to affect their lives. Again, this does not mean completely neglecting the broader national context. Where possible, try to draw connections with federal and state laws, local government guidelines, or demonstrate how the issue can affect broader society.

Finally, as in all journalism work, check your facts. Oral history can be powerful, but make sure key facts are verified to be true, and anecdotes can be corroborated.

In a situation where the interview subjects are also the journalist’s neighbours, it makes it necessary for the journalist to be a good neighbour in order to excel as a journalist. After all, no one wants to be interviewed by an annoying neighbour. In my experience, accepting the responsibilities of both roles with sincerity and honesty (not merely paying them lip service) was a key part in producing a compelling story.

Beyond the story, this approach forms lasting friendships with neighbours that improves the quality of life for the neighbourhood.

At the same time, the usual journalism standards must continue to apply. The reporting must be objective, and offer factual and contextual accuracy. Take every opportunity to help neighbours understand these standards.

Throughout the reporting process, I tried to keep neighbours updated on the story’s progress, as much as I could. Ahead of publishing, I notified all the neighbours, and even organised advance viewings of the story and short documentary for those I interviewed. I shared the trailer and poster on the apartments’ WhatsApp group, and answered questions readily.

I feel this helped neighbours recognise this as a ground-up story, coming from the neighbourhood, now going out into the public.

However, it is also important to help neighbours understand that their involvement does not mean editorial control. Neighbours who have been interviewed can withdraw or change their quotes if they feel they have been misquoted, while you and your editor will have the responsibility over the story’s editorial direction, and its factual and contextual accuracy.

Well, you’re still a neighbour in your neighbourhood, so you still have a role to play.

It is widely acknowledged that journalism plays a role as a mediator in modern societies. The most obvious manifestation of this role is in panel interviews or televised debates, where a journalist mediates between opposing viewpoints. However, the role of mediator is more fundamental – as a space for different people to share stories, and in so doing understand each other better.

In producing this story, I have found it helpful to adapt this mediatory role to a neighbourhood setting. This is particularly true in the aftermath of publishing the story, when residents are excited to share their opinions about the story.

When interacting with neighbours who disagreed, I intentionally encouraged them to see things from each other’s perspectives. I avoided the easy way of simply agreeing with everyone.

Even as I was starting my investigations, I made it one of the stated goals of my reporting – to improve neighbourhood relations among residents. I shared this goal with neighbours when I approached them for interviews.

Over time, I found that this approach helped neighbours see me as trustworthy and well-intentioned.

Consider organising a screening event for your neighbourhood, where residents can interact with you and with each other.

Quality reporting always creates a response. Be ready to continue reporting on responses from authority figures, government, and other parties.

In the aftermath of publishing The Apartments With No Entrance, I immediately reached out to all the relevant government figures for a response. I also produced a number of related follow-up stories on the land dispute, which I compiled on one webpage accessible from the main multimedia story.

I found that this gave everyone the sense that journalism will continue to be a watchdog for the neighbourhood, to bring important updates when needed.

Moreover, your initial story might lead to new information coming to light, or informants stepping forward. Be ready for these opportunities.

Ask yourself: What follow-up stories would add new information or perspectives to my initial story that would benefit my neighbourhood?

Find time after publishing to look back on the whole reporting process, and identify key challenges and best practices. Reflect on how these can inform your practice of journalism going forward.

Too many to list! But here are a few points I think are worth highlighting.

The Apartments With No Entrance was produced as a pilot project with grant funding from Penang Institute’s TechCamp Malaysia programme. This meant I had funds to spend time producing it. I was also able to allocate some funding to engage a video editor and web design services.

If you’re an independent journalist, consider seeking out grant funding from journalism or arts grants. Otherwise, you might need to scale down the deliverables to be less resource-intensive.

Mainstream publications in Malaysia are not known to commission work from independent journalists. However, niche or independent publications might be more open. For investigative work, try pitching to The Fourth. For stories related to the environment, try pitching to Macaranga.

If you’re already working at a mainstream publication, follow the tips for pitching to your editor in our earlier section.

During the reporting process, I found that media literacy was not very high among neighbourhood residents. Most saw journalism as another form of publicity, rather than a means of offering objective information and context to the public.

I find that a participatory approach to reporting has helped them understand journalism a little more. Perhaps encouraging journalists to get involved in our respective neighbourhoods could be an organic way to improve media literacy.

If you’re applying for grant funding, consider adding a media literacy component where you organise activities to improve media literacy in your neighbourhood.

I can only assume that disagreements among neighbours are common, in any neighbourhood. The more important the issue, the deeper the disagreements will be. This makes your role as an impartial mediator more important. Remember that your role is not to support the “correct” side. Focus on producing work that leads to solutions for the common good. Consult and interview experts, as their experience and insights will elevate your story above the opposing viewpoints of neighbours. If you’ve done enough research and interviews, your grasp of the facts and context will show, and residents will respect you for it.

The main lesson I learned from this process is the value of being involved in your own neighbourhood. As journalists, our duties often brings us to the top of the power hierarchy, where we get to hold national leaders, institutions, and influential people accountable.

However, our civic responsibility doesn’t start at the top. It starts wherever we are, with whoever we are living with. In my experience, journalism can strengthen community organising at the most granular, local level.

When local communities are strong, we can expect a less top-down approach in policymaking. So get involved, and report!

If you’re interested in producing a neighbourhood story, I’d love to hear from you, and find out how I can support or collaborate with you. Email me at elroiyee@gmail.com .