A shady land sale has left the residents of Sea Park Apartments locked in a decades-long land dispute, with no control over their own homes.

There is an old, hidden apartment complex in Sea Park, Petaling Jaya. It is nestled at the bottom of a dip, enclosed from view by surrounding bungalows and terrace houses, so that only the roofs of its highest floors peek out. Many PJ residents are surprised to hear it exists.

But these apartments are “enclosed” in more ways than one: The original developer of the apartments sold the apartment’s carpark and common areas – which surround the apartment blocks – to an individual, leaving residents in the unusual position of having their homes completely encircled by someone else’s private land.

To go home, residents first need to trespass.

And this new landowner is not exactly a friendly neighbour. Throughout the decades-long dispute over the land, he has sought to restrict residents from using or passing over it. He has obtained court orders, threatened to dig up the land, and even stationed surly men at its entrance to collect “fees”. In 2018, barbed wire was put up around parts of the land.

As the land’s legal owner, these actions are within his rights. However, the residents of Sea Park Apartments are telling a different story.

This story starts in 1977.

1977

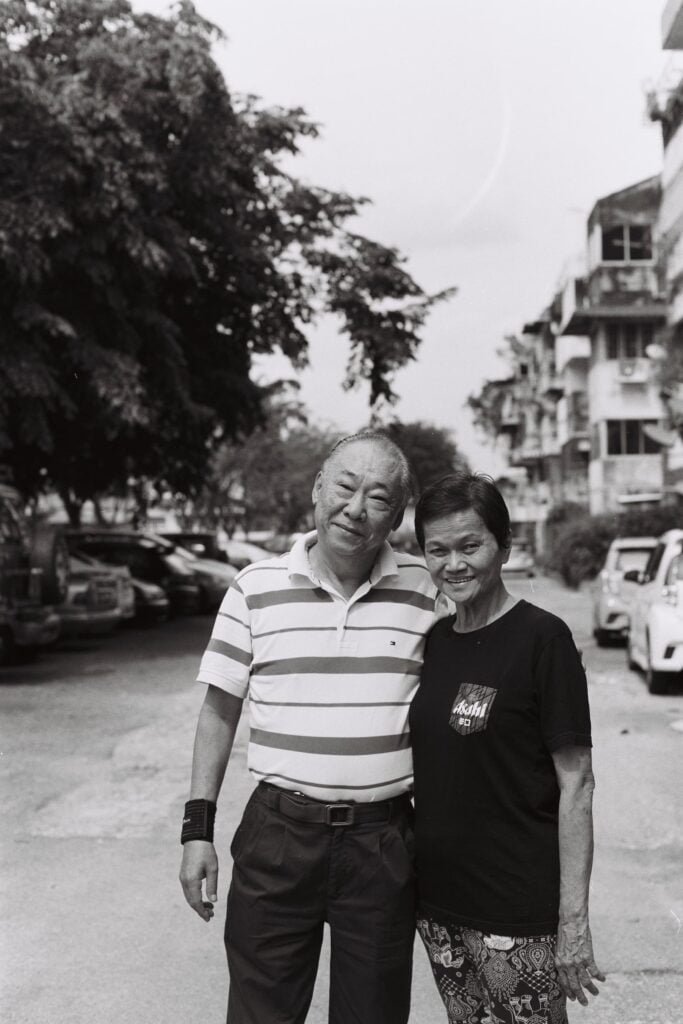

In 1977, or sometime thereabouts, Annie and Gary saw their home for the first time. Annie remembers the romance of that moment. They were both in their late teens, a young couple on the cusp of marriage.

“At the time, my boyfriend here came and took me with his motorbike,” says Annie, with a wave at Gary. “It was all still under construction, but he told me ‘This is where we will stay’.”

“After that, we came to look at it every day.”

“After that, we came to look at it every day.”

Gary has more prosaic memories: “Back there were all plantations then,” he says, pointing in no particular direction to a place in his memory. “We bought the unit for around RM70,000, which was quite expensive in those days, although still cheaper than a landed house.”

Their stories flow and ramble over time and place, as we sit surrounded by a lifetime’s worth of memorabilia, in the living room of that same home they first saw over 45 years ago. It is a small ground floor unit in an apartment complex called Sea Park Apartments.

Built in the 70s and completed in the early 80s, Sea Park Apartments is one of the earliest apartments in Petaling Jaya, if not the earliest, constructed at a time when most residential developments in the area still involved landed properties.

Sea Park Apartments comprises six blocks, each four storeys high, all walk-up with no elevators.

Tap forward to understand how Sea Park Apartments’ lands were subdivided in a way that allowed the developer to retain ownership over the common areas.

Tap forward to understand how Sea Park Apartments’ lands were subdivided in a way that allowed the developer to retain ownership over the common areas.

The entire Sea Park Apartments was developed on 10 separate lots of land. Land records show that these lands were subdivided in 1966, before construction started.

The entire Sea Park Apartments was developed on 10 separate lots of land. Land records show that these lands were subdivided in 1966, before construction started.

The apartments’ six blocks were built on six individual lots.

The apartments’ six blocks were built on six individual lots.

The remaining four lots are common areas surrounding the blocks.

The remaining four lots are common areas surrounding the blocks.

When the developer applied for strata titles for each unit, it made six separate applications – one for each apartment block.

When the developer applied for strata titles for each unit, it made six separate applications – one for each apartment block.

The common areas surrounding the blocks were not included in the strata title applications. Instead, the developer retained ownership of those lands, and insisted those lands were never intended to be part of the deal.

The common areas surrounding the blocks were not included in the strata title applications. Instead, the developer retained ownership of those lands, and insisted those lands were never intended to be part of the deal.

However, there are various essential facilities sited on the common areas, including an Imhoff sewage tank, parking lots, fire hydrants, drains, electrical wiring, rubbish disposal bins, and the security post at the entrance to the apartments.

However, there are various essential facilities sited on the common areas, including an Imhoff sewage tank, parking lots, fire hydrants, drains, electrical wiring, rubbish disposal bins, and the security post at the entrance to the apartments.

Moreover, the common areas surround the blocks completely, and are bounded by a perimeter fence. This strongly suggests that they were meant to be the common property of the apartment residents.

Moreover, the common areas surround the blocks completely, and are bounded by a perimeter fence. This strongly suggests that they were meant to be the common property of the apartment residents.

This situation has left residents with no legal access to their own homes, and no control over the common facilities.

The developer’s decision to retain ownership of the common areas has left residents with no legal access to their own homes, and no control over the common facilities.

Scroll on to continue reading the story of Sea Park Apartments.

Scroll on to continue reading the story of Sea Park Apartments.

Seapark-b

Seapark-a

Surrounding the blocks are open-air common areas, within a perimeter fence.

These common areas are mostly open-air car park bays, but include a garbage disposal area, fire hydrants, and an Imhoff sewage tank that serves the apartments.

The apartments were simple, but modern, located in a residential area just down the street from the neighbourhood’s main commercial area.

Its developer was SEA Housing Corporation Sdn Bhd, which belonged to rubber tycoon Tan Sri Lee Yan Lian, and was then one of the biggest real estate developers in the country, credited with developing neighbourhoods such as TTDI and Taman SEA.

Today, Taman SEA (or Seksyen 21) is a mature, middle-class neighbourhood that is at once nostalgic and gentrified, where age-old kopitiams and hipster cafés thrive side by side. On the northern edge of this neighbourhood is where Sea Park Apartments was built.

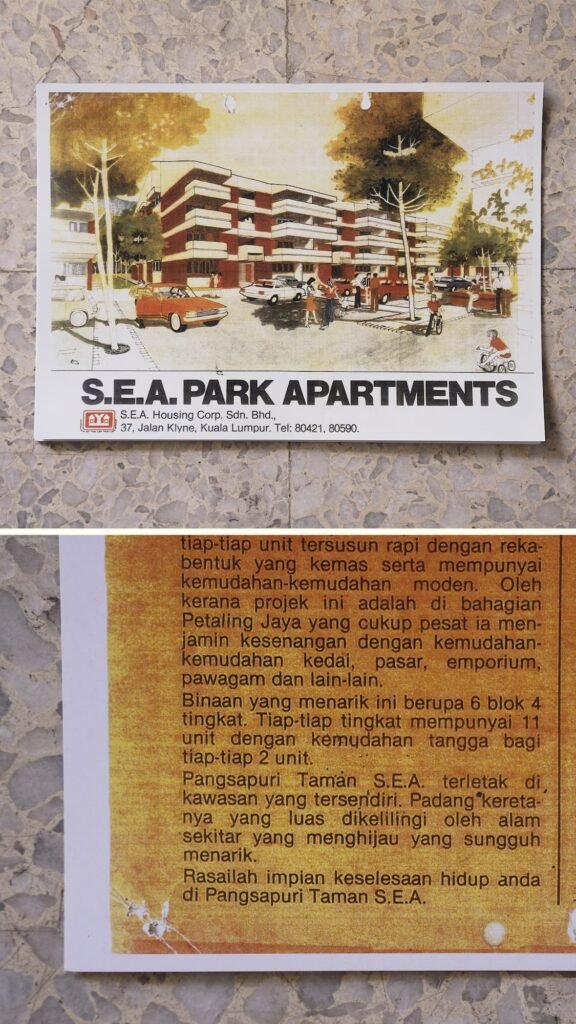

Annie recalls why they decided to buy their home: “Back then there were no model units you could visit, but the drawings on the billboards and brochures all looked very nice.”

She brings out a full-colour copy of the brochure. On its cover is an artist’s impression of the apartments – classy blocks overlooking a spacious, tree-lined common area and carpark, alive with mingling neighbours.

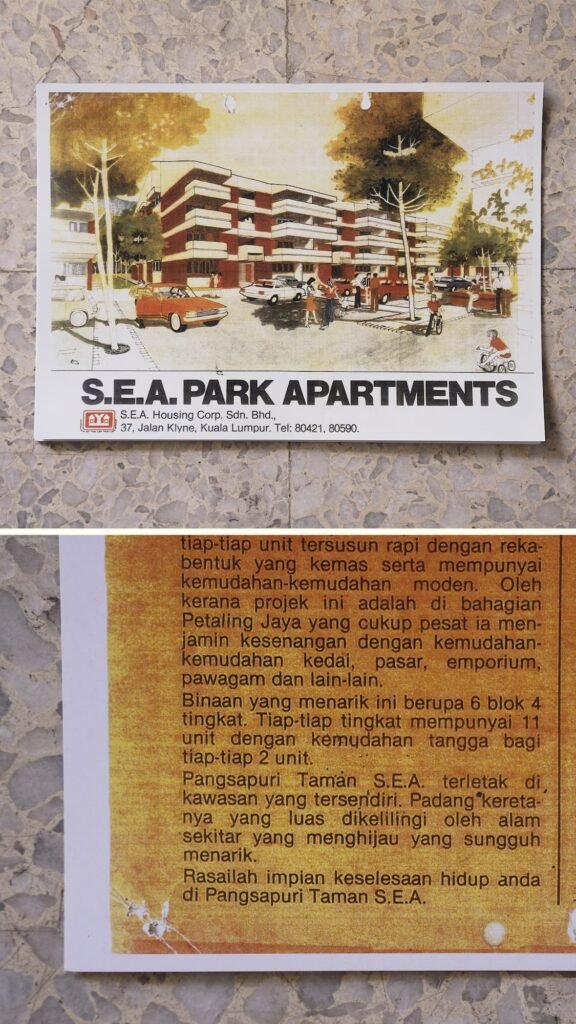

Accompanying text describes the apartments as an “almost enclosed development”, with “ample car parks available”, and “tree-dotted common areas”.

It all sounded promising enough for Annie and Gary. They bought a ground-floor unit, moved in three years later, and lived in peace for the next 20 years.

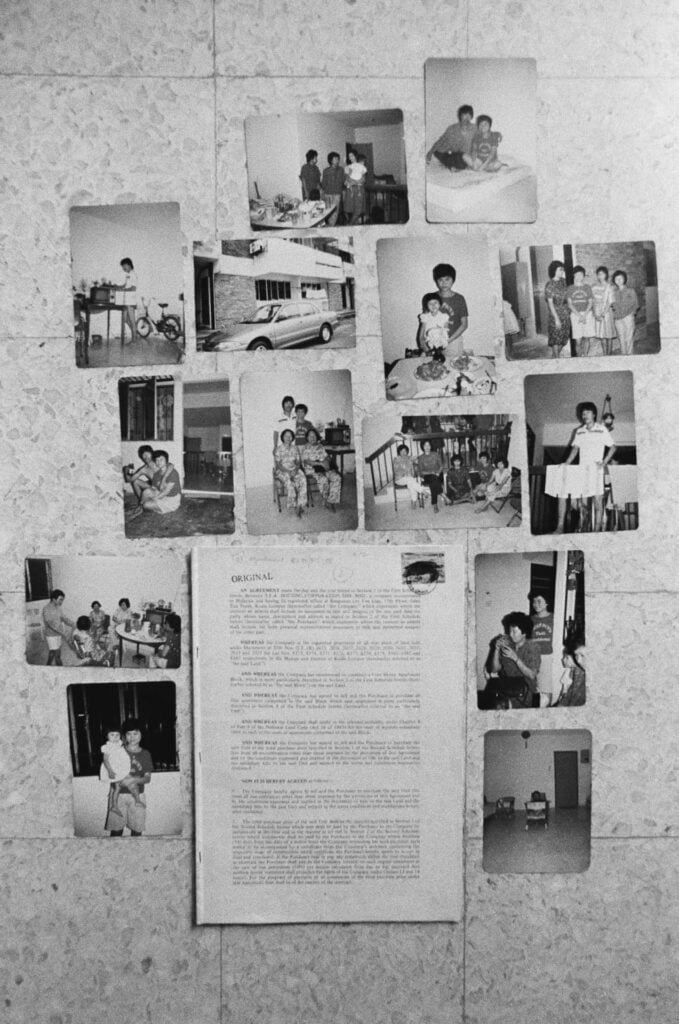

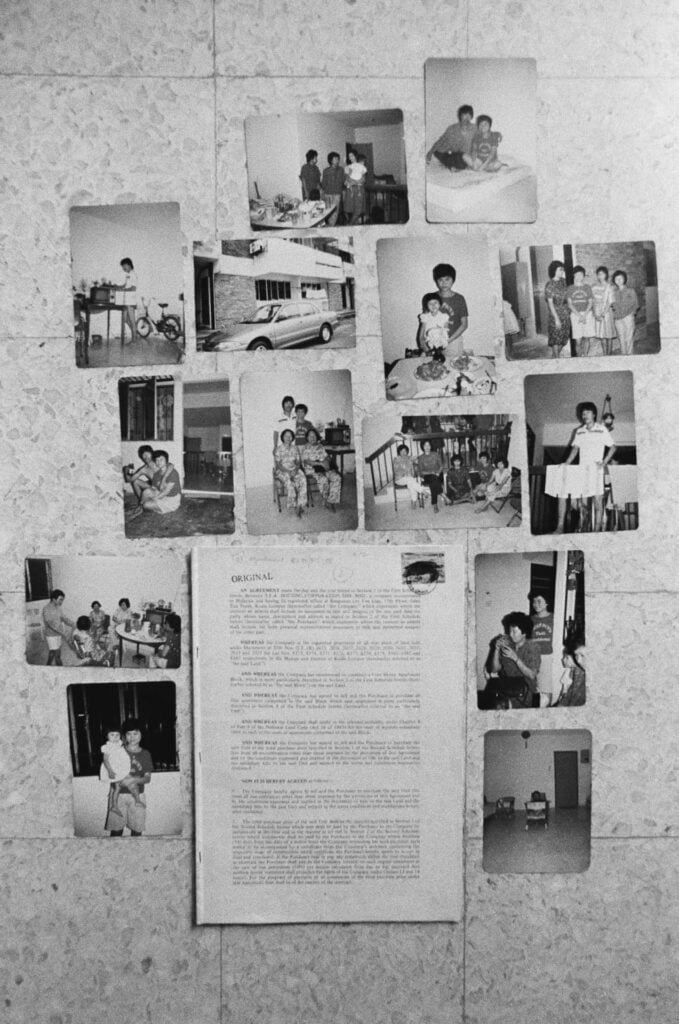

During that time, they married each other, had a daughter, and even spent some time in the United States. A typical suburban life.

“Ours was a classy place back then,” they say, talking over each other recounting those years. “Our security guards patrolled with a ‘K9’, those German Shepherd-type dogs.”

“Ours was a classy place back then,” they say, talking over each other recounting those years. “Our security guards patrolled with a ‘K9’, those German Shepherd-type dogs.”

During that time, they married each other, had a daughter, and even spent some time in the United States. A typical suburban life.

“Ours was a classy place back then,” they say, talking over each other recounting those years. “Our security guards patrolled with a ‘K9’, those German Shepherd-type dogs.”

Along with the perimeter fence, it made the apartments feel safer compared to the rest of the neighbourhood, they say. A management company appointed by the developer managed the security and maintained the common facilities of the apartments.

But in 2004, their story took a turn.

2004

In 2004, the developer of Sea Park Apartments notified residents that they would need to collectively pay RM1.32 million in exchange for the common areas surrounding their apartments. Including legal fees, the owners of the 264 units would need to pay RM6,050 each.

It turns out that these lands, on which were open-air carpark bays and other common facilities, never belonged to the residents.

“When we first heard this, we were shocked,” says Gary. “Shocked would be putting it mildly.”

Most residents had only just obtained the freehold strata title to their homes a few years prior. This strata title should mean that they had full and final ownership of their unit, as well as rights to the common properties.

But when they revisited their title documents, they found it did not include the common areas nor the carpark surrounding their blocks.

This meant residents had no way to access their homes without first trespassing on private property, and no control over the common facilities sited on that private land. Most important of these facilities is the Imhoff sewage tank that processes the apartment’s sewage, but also includes parking lots, fire hydrants, drains, electrical wiring, rubbish disposal bins, and the security post at the entrance to the apartments.

Tap forward to understand how Sea Park Apartments’ lands were subdivided in a way that allowed the developer to retain ownership over the common areas.

Tap forward to understand how Sea Park Apartments’ lands were subdivided in a way that allowed the developer to retain ownership over the common areas.

The entire Sea Park Apartments was developed on 10 separate lots of land. Land records show that these lands were subdivided in 1966, before construction started.

The entire Sea Park Apartments was developed on 10 separate lots of land. Land records show that these lands were subdivided in 1966, before construction started.

The apartments’ six blocks were built on six individual lots.

The apartments’ six blocks were built on six individual lots.

The remaining four lots are common areas surrounding the blocks.

The remaining four lots are common areas surrounding the blocks.

When the developer applied for strata titles for each unit, it made six separate applications – one for each apartment block.

When the developer applied for strata titles for each unit, it made six separate applications – one for each apartment block.

The common areas surrounding the blocks were not included in the strata title applications. Instead, the developer retained ownership of those lands, and insisted those lands were never intended to be part of the deal.

The common areas surrounding the blocks were not included in the strata title applications. Instead, the developer retained ownership of those lands, and insisted those lands were never intended to be part of the deal.

However, there are various essential facilities sited on the common areas, including an Imhoff sewage tank, parking lots, fire hydrants, drains, electrical wiring, rubbish disposal bins, and the security post at the entrance to the apartments.

However, there are various essential facilities sited on the common areas, including an Imhoff sewage tank, parking lots, fire hydrants, drains, electrical wiring, rubbish disposal bins, and the security post at the entrance to the apartments.

Moreover, the common areas surround the blocks completely, and are bounded by a perimeter fence. This strongly suggests that they were meant to be the common property of the apartment residents.

Moreover, the common areas surround the blocks completely, and are bounded by a perimeter fence. This strongly suggests that they were meant to be the common property of the apartment residents.

This situation has left residents with no legal access to their own homes, and no control over the common facilities.

The developer’s decision to retain ownership of the common areas has left residents with no legal access to their own homes, and no control over the common facilities.

Scroll on to continue reading the story of Sea Park Apartments.

Scroll on to continue reading the story of Sea Park Apartments.

Tap forward to understand how Sea Park Apartments’ lands were subdivided in a way that allowed the developer to retain ownership over the common areas.

Tap forward to understand how Sea Park Apartments’ lands were subdivided in a way that allowed the developer to retain ownership over the common areas.

The entire Sea Park Apartments was developed on 10 separate lots of land. Land records show that these lands were subdivided in 1966, before construction started.

The entire Sea Park Apartments was developed on 10 separate lots of land. Land records show that these lands were subdivided in 1966, before construction started.

The apartments’ six blocks were built on six individual lots.

The apartments’ six blocks were built on six individual lots.

The remaining four lots are common areas surrounding the blocks.

The remaining four lots are common areas surrounding the blocks.

When the developer applied for strata titles for each unit, it made six separate applications – one for each apartment block.

When the developer applied for strata titles for each unit, it made six separate applications – one for each apartment block.

The common areas surrounding the blocks were not included in the strata title applications. Instead, the developer retained ownership of those lands, and insisted those lands were never intended to be part of the deal.

The common areas surrounding the blocks were not included in the strata title applications. Instead, the developer retained ownership of those lands, and insisted those lands were never intended to be part of the deal.

However, there are various essential facilities sited on the common areas, including an Imhoff sewage tank, parking lots, fire hydrants, drains, electrical wiring, rubbish disposal bins, and the security post at the entrance to the apartments.

However, there are various essential facilities sited on the common areas, including an Imhoff sewage tank, parking lots, fire hydrants, drains, electrical wiring, rubbish disposal bins, and the security post at the entrance to the apartments.

Moreover, the common areas surround the blocks completely, and are bounded by a perimeter fence. This strongly suggests that they were meant to be the common property of the apartment residents.

Moreover, the common areas surround the blocks completely, and are bounded by a perimeter fence. This strongly suggests that they were meant to be the common property of the apartment residents.

This situation has left residents with no legal access to their own homes, and no control over the common facilities.

The developer’s decision to retain ownership of the common areas has left residents with no legal access to their own homes, and no control over the common facilities.

Scroll on to continue reading the story of Sea Park Apartments.

Scroll on to continue reading the story of Sea Park Apartments.

Now, the developer’s actions are legally correct. According to the Strata Title Act 1985, strata titles can only be applied within the lot of land the property sits on. Since each block is built on separate lots, the developer made six separate applications. These applications were duly approved by the state Land Office, after being checked by the local council (MBPJ), and after the Department of Survey and Mapping (JUPEM) produced strata plans.

Moreover, the sales and purchase agreements signed between the first buyers and the developer explicitly excluded car park bays from being part of the apartments’ common property, unless “the developer, at its discretion, decides to do so, or is required to do so by law.” Since most of the disputed lands consist of car park bays, and with no laws requiring the developer to include car park bays with apartment units, that clause in the agreement protected the developer.

[Browse an original sales and purchase agreement for a Sea Park Apartments unit]

All very legal, yes, but some residents felt cheated. The lands, shaped as they are within a perimeter fence, were clearly meant to be common areas for the apartments. Moreover, the apartments were originally marketed as an integrated development, not individual blocks. Remember that brochure that convinced Annie and Gary to take the plunge?

“If we did not own the car parks, they should have told us from the beginning,” huffs Gary. “Instead they surprise us with this 20 years after we moved in.”

Almost all the residents interviewed expressed similar sentiments.

“We weren’t told we owned the parking lots, but the allusion was there, that we owned the lots,” says Carol, a resident since the late 90s.

“We all had assigned lots, and we’d be very upset if we came home to find someone else parking in our lot. In fact, we would call the security guards who would clamp the car’s tyre.”

“We all had assigned lots, and we’d be very upset if we came home to find someone else parking in our lot. In fact, we would call the security guards who would clamp the car’s tyre.”

Parking, security, building maintenance – all were managed by a single property management company. Sea Park Apartments was not only marketed as an integrated development, it was managed as such. Meeting minutes between residents and the management company attest to this, showing them working together to manage the upkeep of all blocks, as well as the facilities on the common area.

However, land records show the common areas to be separate lots of land, owned by the developer. And the developer, at their discretion, wanted to monetise the property.

The developer’s current General Manager declined interview requests.

“The problem is this – the date,” says Dr Tan Liat Choon, a Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM) lecturer specialising in land law, who had worked for over a decade with JUPEM before.

“The apartment was built in the 70s, when laws on strata development were not so comprehensive yet.”

At that time, there were no specific laws governing strata developments, and titles were issued as subdivided lands under the National Land Code. As high-rise living surged in popularity, the Strata Title Act was passed in 1985, followed by the Building and Common Property Act in 2007, which was repealed and replaced by the Strata Management Act in 2013.

The Uniform Building By-Laws 1984 would have ensured no services – including sewerage, electrical wiring, and drainage – are built on separate private land.

Along with these new laws, were new local council regulations that grew more comprehensive over time.

“According to today’s regulations, a development like Sea Park Apartments on 10 separate lots of land would never be approved,” says Dr Tan. “The developer would first need to amalgamate the land into one lot, before construction.

“People’s homes need to have access roads, strata developments need to have common properties, with all the necessary services within one scheme.

“There was a chance for the developer to amalgamate the land before applying for strata titles, but what incentive would there be for them to do so?”

“People’s homes need to have access roads, strata developments need to have common properties, with all the necessary services within one scheme.

“There was a chance for the developer to amalgamate the land before applying for strata titles, but what incentive would there be for them to do so?”

According to records, Sea Park Apartments’ strata titles were applied in 1997, and issued in 2000.

With the developer’s stance made clear, residents needed to make a decision: pay the developer RM1.32 million, or lose control of their common areas.

After some discussions, a decision was reached in 2006. Or so it seemed.

2006

In 2006, at a Sea Park Apartments residents’ annual general meeting (AGM), a resolution was passed to purchase the common areas from the developer, with the management corporation (MC) of Block A designated as the official purchaser, according to meeting minutes.

This decision requires some unpacking: For the common area lands to be transacted, each lot needed to have a purchaser. Ideally, there would be only one MC representing the interests of the entire Sea Park Apartments, as the formal purchaser of all four lots.

Instead, because the developer made separate strata title applications for each block, there were six MCs that needed to purchase four lots of land that surrounds all six blocks equally.

For reasons unknown to current residents, the MC for Block A was decided upon as the official purchaser – a decision that would ultimately collapse the sale.

In this arrangement, all residents would pay their share of RM6,050 to a law firm engaged to handle the transaction, but upon completion of the transaction, the MC for Block A (officially known as “Perbadanan Pengurusan Apartment Sea Park Block A”) would be registered as the title holder.

Although this was a decision agreed to by all six MCs, many residents disagreed. It seems there was some distrust in the MCs as representatives of the residents. Participation in MC proceedings back then was low, with a few former MC committee members admitting they had to be coaxed into attending meetings to fulfil meeting quorums, where they were then persuaded to put their names up as committee members, and subsequently did not actively participate in decision-making.

“We felt (their plan) was not secure,” explains Gary. “What if dishonest people came to control the MC for Block A, and decided to sell off the land? We’ve already been surprised by the developer once, so we just felt it was not secure.

“We are open to purchasing the land, but the parking lots should be made part of our strata title, as an accessory parcel.”

Thus, the “Special Action Team” was formed – a group of residents who were sceptical of the developer’s deal.

They met almost nightly at Gary’s home, weighing options, and writing letters to seek answers from local authorities. At the same time, they persuaded their neighbours to reject the deal.

Elvira, a resident since 1990, remembers having paid her share of RM6,050, but demanded a refund upon hearing their arguments

“At the time, the parking lot was very important for me, because my father was aged and had difficulty moving.” Elvira’s parking lot was just outside her unit.

“But after hearing the Special Action Team, I felt it was not secure to have the (Block A) MC own the land.”

“But after hearing the Special Action Team, I felt it was not secure to have the (Block A) MC own the land.”

Many others followed suit. According to Annie, some 70% had already paid their share when the deal collapsed. The law firm had to refund the monies to each individual owner. They did not refund the legal fees of RM1,050 each.

It was an impasse, insurmountable even after the developer lowered their asking price to RM840,000 inclusive of one apartment unit which was used as the management office. Until 2008, when the developer found a way out.

2008

In 2008, the developer announced to residents the sale of the common areas to an individual, making good on a threat they issued a year prior.

With the sale, they were no longer responsible for the apartments.

The selling price: RM400,000 for the common area and one apartment unit which was used as the management office – less than half the developer’s final offer to residents.

At that time, residents were still awaiting clarity from local authorities. Correspondence records show letters and emails from residents doing a bureaucratic bounce between different departments in the Land Office and local council.

The individual who purchased the disputed lands is Yap Say Tee, who once managed a hotel owned by the developer, and was earlier approached by the developer to manage the car park at Sea Park Apartments.

With this transaction, the common area lands, and by extension the common facilities sited on those lands, are now owned by Yap. An entire neighbourhood is at his mercy.

Yap, his lawyer, and the developer all declined interview requests.

With the developer’s sale of these lands to Yap, the rules of the game changed: The developer is no longer the registered owner of the disputed lands nor responsible for addressing the remonstrations of the residents, which reached a peak in 2013.

2013

It was a Saturday morning, July 27, 2013, when an excavator appeared at Sea Park Apartments. Without local council permission, it broke earth in the east end of the common area, next to the rubbish disposal bins.

Annie, alerted by neighbours, remembers being the first on the scene.

“It was very early, at 7am,” says Annie. “Yap Say Tee’s lawyer was there, very fierce, saying he wanted to plant flowers on the land and telling us to remove our cars or he will dig them up too!”

Annie chuckles. “I told him: ‘If this is really your (client’s) land, you don’t have to ask, just go ahead and dig up the cars!’”

Annie chuckles. “I told him: ‘If this is really your (client’s) land, you don’t have to ask, just go ahead and dig up the cars!’”

The commotion grew. By the end, neighbours, local council officers, police and the residents’ lawyer had joined the crowd, gathering around a new pothole in the asphalt.

It was the culmination of an escalating conflict. Months prior, in February, Yap had put up notices around the apartment, asking residents to vacate the parking lots.

Within weeks, he filed a suit against the residents, demanding vacant possession of his lands. A court order was issued, allowing him to evict anyone and anything from the disputed lands. At this point, residents began seeking legal advice.

In late July, hired men appeared at the entrance to the apartments, stopping cars as they exited and demanding money. One resident got into a scuffle with them, and lodged a police report. Many other residents did the same. The very next day, a lawyer acting on behalf of the residents filed for a stay of execution, pending their own legal action.

While the stay application was being processed, an excavator was brought in, a pothole made, heated words exchanged, and a years-long court battle began in earnest.

I was only able to catch the tail end of it.

2017

In January 2017, I moved into Sea Park Apartments as a rental tenant. I wanted a simple apartment that didn’t symbolise wealth through insular security measures and showy facilities. Who needs an infinity pool, except so people know they have one?

Sea Park Apartments fit the bill. I also liked the terrazzo floors, the split level interior, the wide balcony, and the quiet neighbourhood. The neighbours, I grew to like, after considerable effort.

My first year here was uneventful. My job as a journalist kept me out of home often.

Drama began in the second year, in 2018.

I returned one day from work to a notice in my mailbox, advising residents to vacate the parking lots. Residents responded by self-organising their cars to park on the access road, leaving just enough space for a single vehicle to pass.

The access road, which runs through the middle of Seapark Apartments, was thought to be a public road, under the control of the local council.

Soon, barbed wire appeared around the parking lots. In a family neighbourhood, it seemed, to me, irresponsible. Perhaps some sense prevailed, as the barbed wire was later replaced by concrete barricades.

At the same time, hired men once again appeared at the gates. They would stop me as I drove out to work, asking for RM10. I asked if they were police, and drove on.

By this time, the resident’s suit against Yap Say Tee, the developer, and the Land Office had failed at the High Court, and Court of Appeal. They would eventually fail to gain leave to appeal at the Federal Court, exhausting all legal avenues.

Each unit owner had paid RM1,200 to the MC, towards the lawyer’s fees. The lawyer who represented them did not respond to multiple requests for an interview.

In arriving at this decision, the courts referred mainly to the land titles, which clearly list Yap as the landowner, and the original sales and purchase agreements which explicitly excluded parking lots from the “common area”, citing it as proof that residents had prior knowledge when buying their homes.

I spent four months looking through documents, and speaking to various experts including lawyers, Land Office officers, and researchers.

Almost all whom I spoke to think the developer has behaved irresponsibly, but agree that the developer and current landowner’s positions are completely legal.

Almost all whom I spoke to think the developer has behaved irresponsibly, but agree that the developer and current landowner’s positions are completely legal.

“By definition, common property belongs to the MC, and cannot be sold off by the developer,” says Raymond Mah, managing partner of MahWengKwai & Associates, a law firm with vast experience in strata title law. “However, we have seen situations where property developers have sought to remove certain areas from common property.

“We’ve seen two approaches – one is to obtain strata titles over an entire car park floor, another approach is by accessorising all the car park bays to the strata title of one of the units.”

In one case Mah’s firm was involved in, hundreds of car park bays were accessorised to only a handful of apartment units. The developer then sold the car parks by selling those units, leaving none for the other units.

Mah says court decisions on these cases have been mixed – some favouring residents, some favouring the developer.

However, the situation in Sea Park Apartments is different. The common area lands are under a different land title, and the developer technically never included it as the apartment’s common property. On paper, it has remained private property since it was subdivided in 1966.

Land ownership in Malaysia is based on the Torrens system, which was developed by colonial British administrators in Australia. According to this system, the government maintains a central registry of all land ownership and transactions. This registry is the final authority on land ownership, and all land disputes are resolved by checking who is the registered owner of the land in the registry. Unless it can be proven that the title was registered through unlawful means, ownership is considered “indefeasible”, and the landowner has the right to sell or lease the land as they please.

“Since the lands were already subdivided as such, prior to construction, there was very little that could have been done (by the local authorities) to prevent the sale,” says Mah.

Neither were there other documents to contest the developer’s assertion that the lands were meant to be developed separately. The marketing brochure was presented in court, but held little legal weight.

Building plans – which need to be submitted to the local council to obtain approval before construction – would have laid out which lands are part of the development, and how they will be used.

But in the case of Sea Park Apartments, these building plans have disappeared.

Neither the local council, the Land Office, nor the developer have been able to produce the plans, which would likely have been submitted in the 60s or 70s.

But in the case of Sea Park Apartments, these building plans have disappeared.

Neither the local council, the Land Office, nor the developer have been able to produce the plans, which would likely have been submitted in the 60s or 70s.

With the court decisions affirming the indefeasibility of Yap’s land ownership, any further legal action by the residents against him is unlikely to succeed, says Mah.

“One way out is for the state authority to acquire the land for public interest, under the Land Acquisition Act 1960,” says Mah. “If the state refuses to do so, one option is for residents to take the state authority to court by way of a judicial review.” Mah pauses before adding bleakly: “But that would be another long story.”

When interviewed, Lim Yi Wei, the state legislative representative for Sea Park Apartments’ constituency, said that the state government is unlikely to acquire the lands, to avoid setting an expensive precedent. Lim has also tried mediating the dispute, but she claims Yap’s lawyer declined the meeting.

“It essentially comes down to a conflict on who owns the land, and who has the rights to use it,” she says. “Under the law, (Yap Say Tee) has all the rights. There is nothing to stop him from… blocking people from using his land.”

“The tricky situation is that there are people living around there, who bought into this idea (that their apartments would include common areas). These people are there, and you cannot move them away.”

“The tricky situation is that there are people living around there, who bought into this idea (that their apartments would include common areas). These people are there, and you cannot move them away.”

2023

In April 2023, Sea Park Apartments lost more land.

Courts ruled, in a separate case, that even the access road running through Sea Park Apartments belongs to the original developer.

It turns out that the access road – a long ring-shaped circle of land – was not a public road as many assumed. It was still titled to the developer.

It started with an effort by local authorities to find a resolution to the land dispute, and chancing upon records showing unpaid land taxes on that particular plot, the Land Office issued a seizure notice, which it is entitled to do when taxes go unpaid for a certain period of time.

But instead of regaining some control over the area, this action ended up affirming Yap’s ownership over the common areas.

The developer delegated power of attorney to Yap, who brought the Land Office to court, and won. Yap’s affidavit claims he had been told by the Land Office that the road overlaps with one of the plots of common area lands, and are one and the same, which is why he did not pay the taxes.

[Browse the court documents for Yap’s suit against the Land Office]

The case is currently under appeal by the Land Office. It is likely to take months, if not years, to resolve.

Meanwhile, Sea Park Apartments is hurtling towards another tipping point.

Imminent

The end of October 2023 is when residents anticipate electricity will stop running to the Imhoff sewage processing tank in Sea Park Apartments.

This is because court decisions against the residents have left them without a functioning MC to pay the utilities bills.

When residents lost their suit against Yap Say Tee, he claimed RM8 million in compensation from the MC for loss of use of his lands. Residents disputed the amount, and hired a valuer to conduct an assessment of the revenue that the land could have generated as a carpark.

The valuer’s assessment of compensation was set at just over RM1 million, which was accepted by the court.

But even this amount was too much for the MC to pay. The MC council members promptly resigned, and Yap’s lawyers had the MC’s bank account garnished. This means no monies can be paid out from that account, except to Yap.

Today, Sea Park Apartments is essentially without management. Cleaning and security services have stopped, the management office is permanently closed.

The land dispute has led to residents losing control over facilities that are essential to urban life.

Electricity and water bills for the common areas, including for the Imhoff tank, were paid in advance, but are anticipated to run out in October. What happens after that, is best left undescribed.

Electricity and water bills for the common areas, including for the Imhoff tank, were paid in advance, but are anticipated to run out in October. What happens after that, is best left undescribed.

It doesn’t stop there. It seems there is a risk residents could even lose the land beneath their homes.

While producing their assessment, the valuer found a glaring error in the title documents for two of the plots of land belonging to Yap. These two lands immediately surround the apartment blocks, and their land areas should amount to 3,168m² and 5,312m² respectively. However, the land title lists their area as 6,820m² and 8,963m², which is an area that includes the footprint of the apartment blocks themselves.

Now, this is clearly an administrative error, but if the title documents are taken literally, they overlap with the title for the land beneath the blocks, which are titled to the MC, and Yap could try to argue ownership.

[Browse the valuation report produced by KnightFrank]

[Browse the repository of all documents related to the Sea Park Apartments’ land dispute]

The Common Good

Dr Suraya Ismail can barely stay quiet as I tell her the long story of Sea Park Apartments.

“Ok, now I’m really getting heated,” she interjects, when she hears that essential services at the apartments have stopped.

To most, Sea Park Apartments is a quirk. An anomaly. Something that would never happen under modern laws.

But Dr Suraya sees it as part of a pattern.

“In all my research over the past 20 years, I’ve yet to see any developers thinking of the common good, of building communities. It is always ‘How much money can I make from my plot of land?’.”

But Dr Suraya sees it as part of a pattern.

“In all my research over the past 20 years, I’ve yet to see any developers thinking of the common good, of building communities. It is always ‘How much money can I make from my plot of land?’.”

Dr Suraya is Research Director at Khazanah Research Institute (KRI). Before joining KRI, Dr Suraya was Programme Director at ThinkCity, supporting urban rejuvenation activities through grant funding. Prior to that, she was Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Built Environment at Universiti Malaya. Today, aside from her role at KRI, she sits on a panel of experts advising the Ministry of Housing and Local Government.

Before all that, she spent worked in the construction sector, where she witnessed first-hand the unsavoury tactics sometimes unleashed on communities in the name of development. She confides some shocking examples, which she prefers to keep off-record. She left the industry after two years.

“That was it,” she says. “I couldn’t go on.” She pursued research instead, setting her on the path that brought her to KRI, where she is now putting her experience to bear. She recently co-authored two research publications on housing in Malaysia – one focusing on spatial inequalities in Klang Valley neighbourhoods, the second on Malaysia’s social housing schemes.

“If we look at property rights (in Malaysia), if you don’t own the land, you don’t have a say on the land. So ownership has become the backbone of city-making, unfortunately.”

There are increasingly stricter regulations for landowners and property developers, along with structure plans to ensure holistic development of land, but developers often push them to the limit.

“One example is affordable housing. When developers are required to build houses within the affordable range, some choose to deliver poor quality units of, say, 450 ft². That’s hijacking the standards of what makes a liveable house.”

In strata developments, she finds many developers strive for higher density. It makes business sense: the more units that can be placed on one plot of land, the higher the profit.

But a denser population means less space for common facilities, or common facilities that will be overused, leading to high maintenance costs. This creates a neighbourhood that doesn’t want the stress of participating in maintenance.

Over time, things break down. The community breaks down. This, says Dr Suraya, is how urban slums are created.

“In the government social housing schemes (PPRT) we studied, maintenance was poor because of a lack of resources from the government.

“But in Sea Park Apartments, it is because something outrageous has been done to the residents. With the facilities on private land, access road on private land, the property value will go down, and residents will have no agency.

“This is, I think, an infringement on human rights. And if the legalities support this situation, I think we should think of changing the legalities.

“If the law is technically unsound, there must be a way to argue for the common good.”

“This is, I think, an infringement on human rights. And if the legalities support this situation, I think we should think of changing the legalities.

“If the law is technically unsound, there must be a way to argue for the common good.”

Dr Suraya has seen examples in other countries, where property prices are purposely driven low enough to be acquired for redevelopment, and an extra round of profit. Of course, no one knows if that is indeed Yap’s intention.

What can residents do? I ask. She takes a long pause, visibly considering the options in her mind.

“(With the High Court decision), I don’t think there is anything the residents can do at the moment,” she finally says. “But I do know the effect it will have on property developers. They will start thinking they can make a killing by privatising roads and car parks (by placing them on private land), and then press residents to pay more for these services.”

She explains at length the possible permutations, all of which lead to weak maintenance, disenfranchised residents, lower property prices, and poorer liveability of the neighbourhood.

But residents can break what she calls “the vicious cycle of urban slums”: “I disagree that residents should shrink away when things are tough. It’s when things are tough that we need to get more involved, and try to improve the situation.”

Today

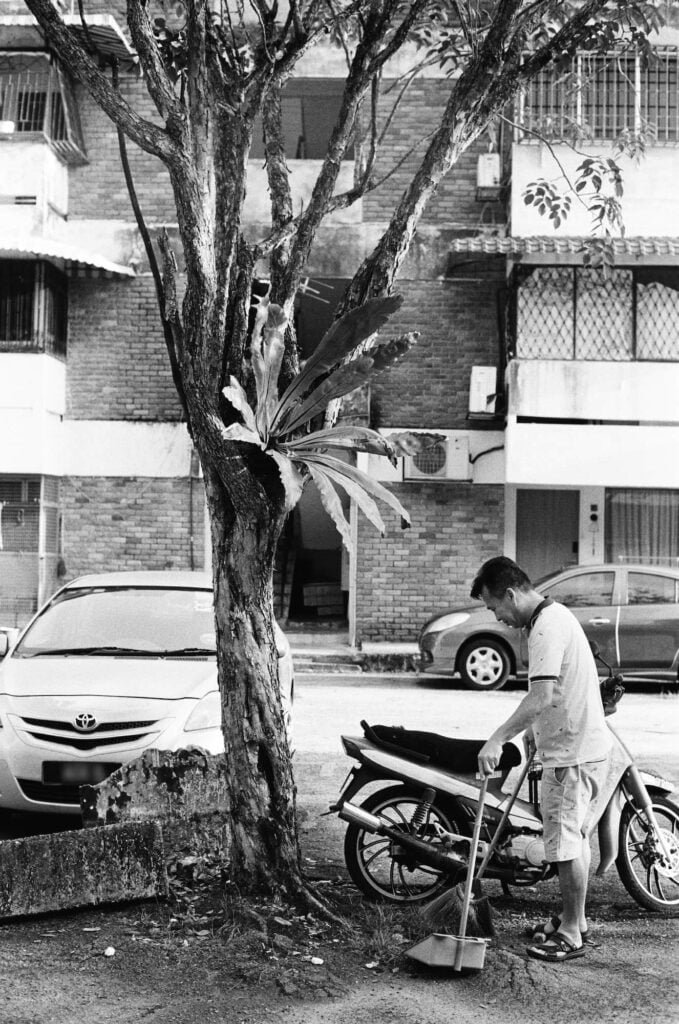

At dusk in Sea Park Apartments, you will hear John sweeping the street and carpark downstairs. He does it almost every day, since cleaning services stopped, sweeping the entire stretch in front of Block B and C. He bags the dried leaves, and discards them at the communal garbage disposal bins.

“Might as well loh,” he says, when I ask why.

“Might as well loh,” he says, when I ask why.

At the garbage disposal bins, a mother-and-son team sometimes picks up the bits of rubbish that fall outside the bins. They smile shyly when I say thank you.

At dawn, you sometimes hear Le filling up the potholes on the access road. He scrapes the soil and sand that accumulates in rain-washed piles, and tamps the road flat. He also keeps the back fence of the apartments impressively landscaped with a variety of plants.

Some mornings, you find Sally teaching Qi Gong to the neighbourhood ladies. Her son, Keith, volunteered as MC chairperson for two years during the pandemic, trying to organise residents who watched him grow up towards a solution to the land dispute. He often shuttles between Singapore, where he works, and Sea Park to attend to apartment matters.

Then every now and then, you hear Annie and Elvira chattering as they set off in Annie’s old Kancil to meet local authorities or government departments, to hand them documents of note or letters asking for help to resolve this land dispute that has entered its 19th year, and counting.

“I just think I have to do whatever I can, for everyone’s benefit,” says Annie.

Gary has more practical motivations: “We are already old, so we just hope this issue is resolved and we don’t have to pass the headache down to our daughter.”

Gary has more practical motivations: “We are already old, so we just hope this issue is resolved and we don’t have to pass the headache down to our daughter.”

Residents like Keith, Annie, Gary, and many others continue to seek a solution to the dispute. Their engagements with local authorities led to an attempt by the Commissioner of Buildings (COB), the unit in the local council that oversees strata developments, appointing a management company to resume essential services in Sea Park Apartments. However, that solution failed to take off: the appointed company withdrew to avoid getting entangled in a complicated dispute.

They are now seeking alternatives, including possibly negotiating a compromise with Yap.

“The fact that the apartments has not descended into a health and sanitation catastrophe is a testament to the residents here, that we are taking care of each other,” says Keith. “But we can’t go on like this, we need to try new strategies to move forward.”

Would you rather sell the apartment and move elsewhere?

“We don’t really have plans to move out at the moment, my mother is supremely proud of this home,” says Keith. “But who knows what the future holds?”

“Not everyone is rich and has the money to move,” says Annie. “And I don’t know, I feel like I’ve developed feelings for this Sea Park Apartments. We’ve lived here for over 40 years. Of course there are feelings.”

NOTE: This story is produced with grant funding from Penang Institute’s TechCamp programme, as part of a project to promote hyperlocal journalism within neighbourhoods. The author is a rental tenant at Sea Park Apartments.

Credits

STORY BY

Elroi Yee

WEB DESIGN

Husna Ab Rahman

WEB DEVELOPMENT

Yasmin Zulhaime

MANDARIN TRANSLATION

Lam Jun Hui

TRANSCRIPTS

Leong Jie Yu

PHOTOS/VIDEOS

Elroi Yee

THE FOURTH

Ian Yee

CONTRIBUTING RESIDENTS

Annie Loo

Carol Chin

Elvira Fung

Gary Choong

Keith Liu

Sally Lam

SPECIAL THANKS

Cecilia Yap

Christopher Choong

Dr Suraya Ismail

Dr Tan Liat Choon

Foo Hui Ping

Lim Yi Wei

Medaline Chang

Nalina Nair

Nazmi Anuar

Ong Siou Woon

Penang Institute

Puah Sze Ning

Raymond Mah

Seira Sacha Abu Bakar

Sherrie Ab Razak

Terence Goh

The Fourth

Wan Sofiah Wan Ishak

Wong Jeh Tat

PRODUCED WITH SUPPORT FROM

PUBLISHING PARTNER

EXCEPT WHERE OTHERWISE NOTED, THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION NONCOMMERCIAL NODERIVATVES LICENSE